Author reflection: writing ancestor’s biographies

Harriet Susannah Ellis was born on February 5, 1863 in Riverstown, County Sligo, Ireland.

Her oldest surviving son – my Irish-born great-grandfather – lived until I was thirteen. I have fond memories of him – including the time when he fell asleep at my birthday party (I was turning eight) and the party stopped so that the children in attendance could watch him snore with an Irish brogue. When I was three or four, he carried me around his yard in a wheelbarrow – great fun for a young child. I still buy deep purple pansies because he had deep purple pansies in his yard when I was a child.

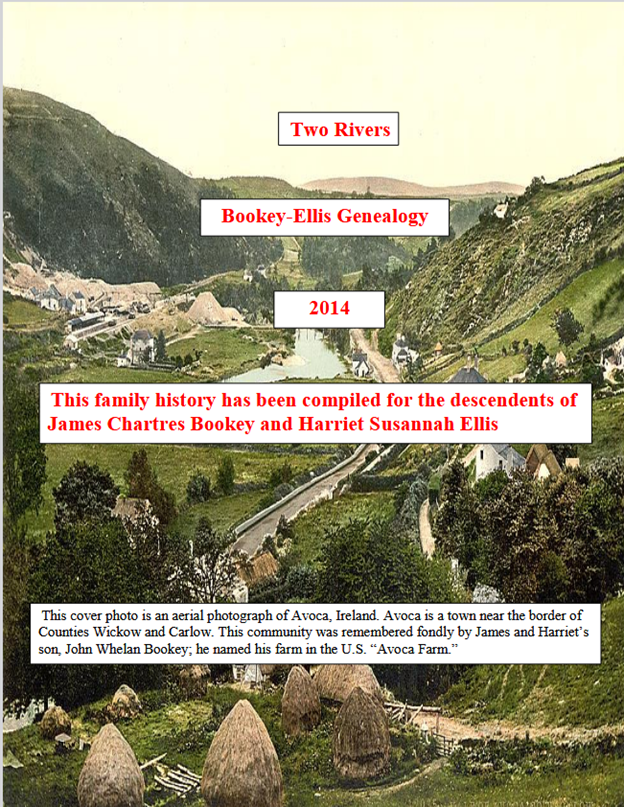

When I was growing up, we heard stories about my great-grandfather’s childhood in rural Ireland (County Wicklow). We heard about his blind father (I, in turn, was raised by my blind mother). We heard about his paternal uncles and paternal grandfather who were doctors (in 2018, I visited Trinity College Dublin where they did their medical degrees in the 1800’s. It gave me chills to realize they had walked the same hallways when I walked through the campus’s historical library).

Yet, I realized in 2013 that I knew nothing about my great-grandfather’s mother. Surely she had existed, confirmed by the fact that she had children whose lives I knew about. I had never heard any mention of her. I didn’t even know her name.

Because we live today in a digital age, I was able to go online in search of information about my great-grandfather’s mother. Within a fairly short time, online genealogical research led me to her name. Harriet Ellis. Specifically, Harriet Susannah Ellis. Beyond that, I didn’t find much. In January, 2014, I decided to do a Google search of her name. Fortunately, I found a post on a genealogy website written by her youngest brother’s grandson. Great! I contacted him.

When I contacted Harriet’s youngest brother’s grandson, it turned out that he lives in a Dublin suburb. Much to my happy surprise, he had been driving around Ireland for twenty years looking up genealogical records of our ancestors (I am fortunate – not every budding genealogist finds such a relative!). He was happy to share the information he had been meticulously collecting.

Fast forward. I began organizing data about my Irish ancestors into book form. I contacted other descendants – collected their info about recent generations. I collected old family photographs, old family letters that had been saved, family stories that had been passed down. All of this became our family’s genealogy book (see my previous post about my Irish genealogy book).

By the time we printed our genealogy book and had the first family reunion since 1980, I had learned much about Harriet’s life. She was born in the same Irish county as William Butler Yeats’ family at about the same time (did she ever cross paths with him?); the county where she was born was also where Bram Stoker’s mother was born (Bram Stoker seems to have gotten several ideas for his Dracula novel from stories his mother told about County Sligo’s cholera epidemic in the 1930’s). Harriet had thirteen children, ten of whom lived. She filled out the birth certificate and the death certificate for her first-born child who died two hours after an unattended home birth. Her father was a school master who moved from job to job, taking his wife and children all over Ireland via Ireland’s newly-emerging train system. She eloped. As the daughter and sibling of school masters, she valued education for her children. She emigrated in the 1900’s. She died the same day that the Soviets invaded Poland. I suggested to my Dublin-area distant cousin that we continue on, writing Harriet’s biography. We did.

Writing Harriet’s biography was made possible as a result of many years of genealogical research. A point I want to stress is that books are often the end-result of much learning and effort. The book was also a labor of love. Writing a book is an effort that requires learning the mechanics of writing (we learn at least some if this in school), learning what’s involved in making information presentable and interesting, and putting in the time to write. Having an editor go through one’s written material helps identify needed improvements before publishing a book (identifying spelling and grammar that need correction, spotting incomplete presentations of information that are overlooked when knee-deep in the writing process, noting shifts in perspective or narrative style that need correction, etc.).

I am also pleased to have contributed to bringing stories of every day historical women’s lives to print. After we published Harriet’s biography, I came up a research network that studies “Perceptions of pregnancy.” I wrote an article for their website about Harriet’s experience of childbearing: An Experience of Home Births in Rural Ireland: 1883 – 1903.

I hope you will take an interest in Harriet’s biography.

Kim Burkhardt provides writing services at Burkhardt Writing Services. Contact us about your wordsmithing needs.